In this post I am going to describe some of the dynamics of the banking panic from an operational perspective. I hope it helps everyone better understand what’s going on today and what might play out in the coming years.

The S&P regional bank index is now down -34% year to date and discussions of a credit crisis are running rampant. Some even worry this is 2008 all over again. In this piece I will explain why this isn’t 2008 all over again, but that the current environment is still very challenging for banks (and the broader economy) and likely to remain this way for the foreseeable future.

We have a mini credit crisis brewing inside parts of the banking system that has yet to spill over into the rest of the economy in a meaningful way. The cause of this mini crisis is the re-pricing of everything in the economy following the COVID boom and bust. As inflation roared in 2021 money became a hot potato as consumers tried to dispose of cash as fast as possible to obtain real goods. This hot potato effect has been driving prices higher as we discover the new price level equilibrium.

The Fed responded to this by re-pricing the overnight rate in the banking system. The goal of this is to reduce this hot potato effect and get the demand for money to increase by increasing the attractiveness of holding cash and reducing the demand for credit. In other words, the Fed is making it more attractive to hold cash and less attractive to take on credit.

There are several ways that this reduces inflation. The monetary policy transmission mechanism works in several ways including:

- The interest rate channel

- The financial crisis channel

- The portfolio rebalancing channel (asset price effects (wealth effects & balance sheet channels)

- The expectations channel

- The credit channel

- The exchange rate channel.

The Fed’s aggressive rate hikes and balance sheet reduction (quantitative tightening) operate thru changing interest rates, rebalancing portfolios, altering expectations and slowing the credit markets. All of this is essential in understanding what banks are experiencing at present.

Your Golden Handcuffs are the Banking System’s Golden Guillotine

Rising interest rates work through the interest rate channel to impact the credit channel primarily. Rising rates make it more expensive to borrow and are intended to reduce inflation through reducing demand for new credit issuance. This is working, but it’s not a pretty process as some banks are the collateral damage along the way.

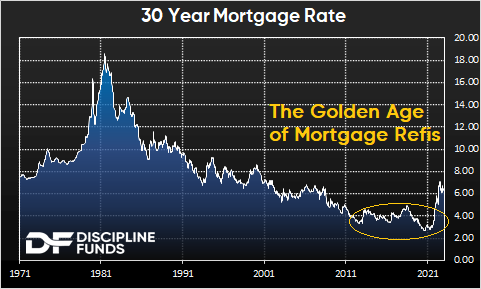

We’ve heard a lot in recent years about low interest rates and “Golden Handcuffs”. Golden handcuffs refer to anyone who borrowed at 3% mortgage rates and how they’re unlikely to roll that mortgage into a 7% mortgage. That 3% mortgage rate looks like the deal of a lifetime compared to the new normal and so holders of those low rate mortgages feel “handcuffed”. But there’s always a counterparty in these transactions and your Golden Handcuffs are a Golden Guillotine for the counterparty of that loan.

The basic thinking here is that someone holds the other side of that golden handcuff trade. And in a world with 5% inflation that 3% mortgage payment is sucking wind. This is the crux of all the mark-to-market losses that banks and other investors are sitting on. In short, the Fed raised rates to combat inflation and as rates rise, bond prices fall. So all of these bonds have been re-priced lower to reflect the new interest rate regime.

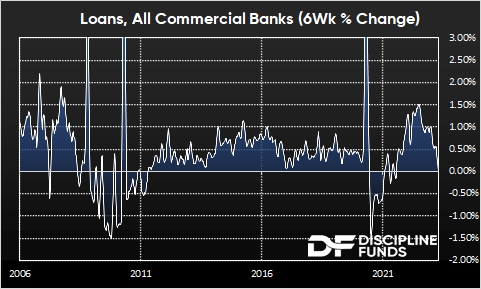

The portfolio rebalancing channel has had a meaningful impact on these banks as they’re not only sitting on losses in their bonds (some estimate these losses are as much as $2.2T), but banks are also working to reset their loan books for this new paradigm. This is a very slow moving process because we had 10 years+ of lending in the 0% overnight paradigm. The problem is, there isn’t a lot of demand for loans in this new paradigm. That’s reflected in the rate of change in new lending.

This data hasn’t moved deeply negative like we saw during COVID or the GFC, but it’s slowing and now flat. So banks are struggling to roll old loans into newer higher yielding loans. More importantly, this is likely to persist given where the Fed is. Our estimate is that rates will remain higher for longer and probably close to 5% or higher through all of 2023. And the longer rates stay at these levels the demand for loans will remain low and banks will struggle to reset their loan books to a more profitable position.

All of this means that the Golden Handcuffs reduce demand for future loans and operate like a Golden Guillotine for some banks who are sitting on large mark-to-market losses and unable to roll their loan books quickly.

The Deposit Hot Potato Effect

High rates don’t just reduce the demand for longer duration loans. They also increase the demand for money and short-term paper. This is the triple whammy for banks because now it becomes more expensive to fund their balance sheets. In short, banks are getting crunched on the long end and all their short-term funding sources just got a lot more expensive.

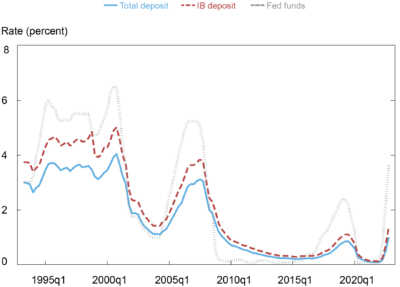

The way this works is that deposits operate like a hot potato in a high inflation environment with a high overnight rate. Bank deposits can’t really leave the system except through loan repayment and Quantitative Tightening.1 So all deposits are held by someone until they’re retired. But in a high inflation environment with a high overnight rate those deposits start seeking out higher yield and put upward pressure on deposit rates. In the old paradigm of 0% interest rates those deposits are very sticky because depositors are indifferent to interest rates. But in a world of 5% interest rates those deposits become unstuck and become flighty until they become stuck to a higher yielding instrument. As investors furiously trade these instruments in the closed system of outstanding deposits, they put upward pressure on bank deposit liability rates until these prices reach their own equilibrium.

Monetary policy operates with famous lags and so does this deposit rate transmission mechanism. As the NY Fed recently described, deposit rates are starting to rise rather rapidly. So banks are getting pressured on both sides of the trade here. Their deposit liabilities are becoming more expensive and they’re either sitting on large asset losses and/or unable to roll those old assets into new higher yielding assets.

The Velocity of Bank Balance Sheets

A good way of thinking about all of this is that there’s a velocity problem for banks and their balance sheets. The Fed raised rates so quickly that they put the entire banking system into a new high rate paradigm when the banking system had grown overly accustomed to the low rate paradigm. So now the banks have to grow into this new paradigm and that process is unlikely to be quick or pretty. And that’s because the velocity of their balance sheets is working against them as their liabilities become expensive very quickly (because depositors can seek yield so quickly) AND their assets are rolling over slowly and/or impaired from the rate hikes.

This process is far from over because there are 10 years worth of low interest rate loans that need to adjust and the Fed is unlikely to reduce interest rates any time soon.

This isn’t 2008 All Over Again

The bad news in all of this is that this sort of environment puts a lot of pressure on banks and the broader economy as credit issuance is likely to be tepid. But the good news is that this isn’t 2008 either. In 2008 you had this same credit crisis within the banking system where rising rates put pressure on banks. But so far we don’t have severe credit impairments outside of the banking system. That’s primarily because the quality of aggregate lending during the COVID boom was far superior to the period before the GFC.

Additionally, we have yet to see severe asset impairments within the real estate market. Prices are down a modest 5% and while we expect them to be pressured further in coming years we do not see the large 30% style declines that contributed to so many problems during the GFC. Instead, we expect this process to be more of a long grinding process like the 2002 re-pricing instead of the panicky 2008 re-pricing. It’s not a fun process, but it’s also not the doom and gloom that many portend.

The Bottom Line

All of this is a classic credit cycle so far and it’s clear that there are real fundamental reasons for today’s problems in the US banking system. And based on past cycles these problems are unlikely to go away any time soon primarily because these problems can’t resolve themselves except with lots of time and adjustment OR a transition back to the old paradigm (ie, rate cuts). At the same time, they do appear largely contained to the banking system. However, risk aversion in the banking system also means that credit issuance is likely to remain slow and that puts overall pressure on the economy. And that’s one of the big reasons why we continue to believe this is a period of “muddle through”. At the same time, investors would be wise to note that environments like this tend to be fraught with asymmetric risk. While muddle through is our baseline outlook the higher for longer environment increases the odds of a sharper contraction in credit than we expect.

1 – Deposits can technically leave through other sources such as RRP, TGA, etc, but loan repayment and QT are the primary ways that this is impacted in a structural manner across the last decade.